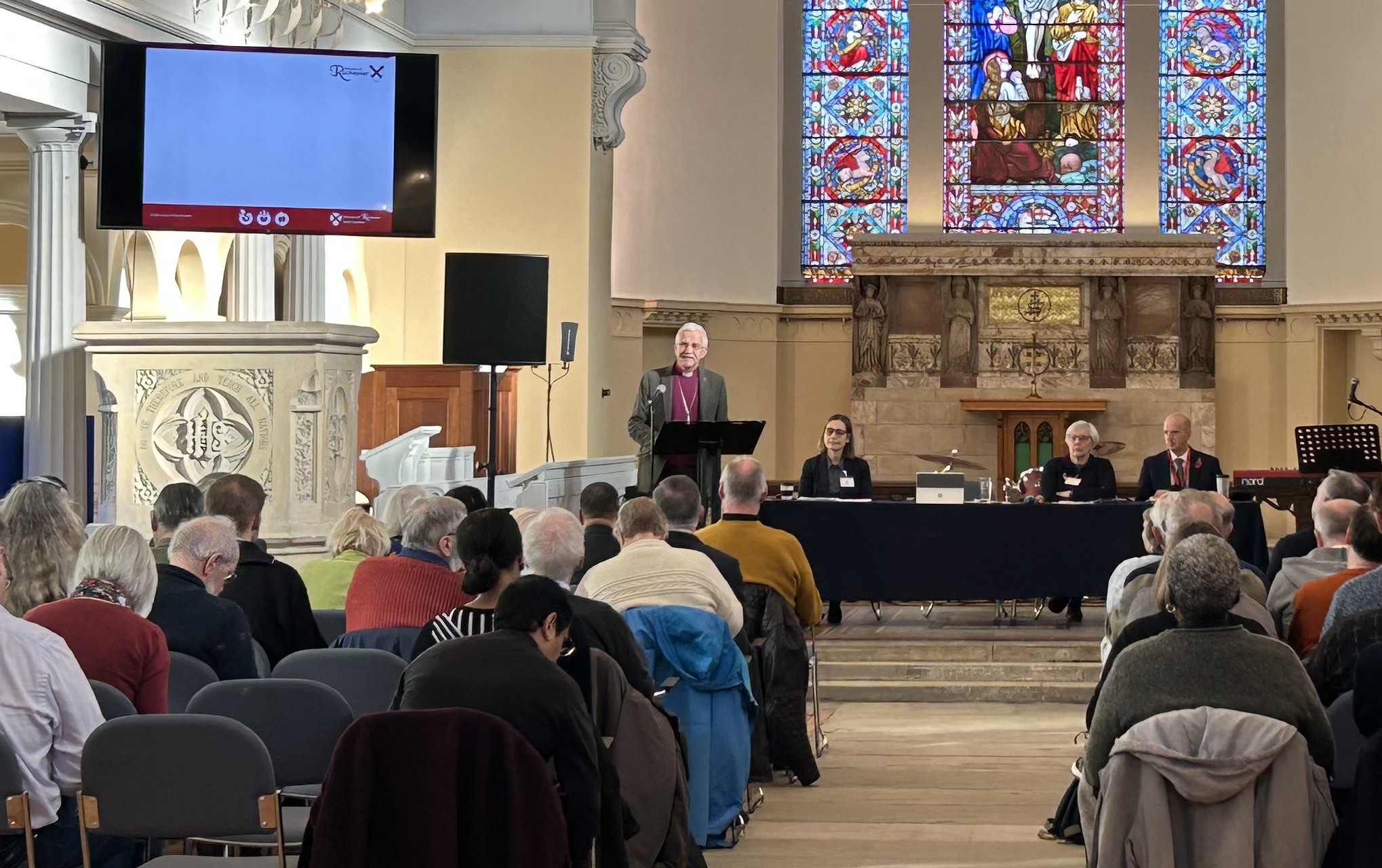

Diocesan Synod met on Saturday 8 November at St John's Chatham. As part of the opening worship, Bishop Jonathan gave his presidential address.

Read it in full below.

Bishop Jonathan's address to Diocese Synod

In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

Good morning. It is wonderful to be here at St John’s Chatham, to see this marvellously refurbished building and to hear more about what God is doing to build his church in this place.

It is very good also to see you all here at our Diocesan Synod this morning, and as you will know a lot has happened since we last met back in July, including the momentous appointment of the first female Archbishop of Canterbury – of which more anon.

As I begin, I have a question for us to consider this morning – a question which is both personal for me and, I believe, relevant to the Church of England as we seek to rise to the challenges facing us at this time. And the question is this: What are bishops for? Let me repeat that: What on earth are bishops for?

This is obviously a personal question for me, having been ordained as a bishop just over eleven years ago.

It is a question for the Church of England, as we wrestle with the complex issues around Living in Love and Faith and the many other challenges facing our Church, including around vocations, clergy numbers and diocesan finances.

And it is also a question for our churches in the wider cultural and social context of Western Europe – what is the role of bishops in relation to that wider culture?

After many years of study and reflection on this question, I would suggest that the answer to this question can be summed up in one short phrase – a phrase that contains many aspects within it, but that takes us to the heart of the question, what are bishops for? And that phrase is this: the purpose of bishops – the principal role to which we are called (alongside others of course) – is to pass on the faith.

Again, let me repeat: the principal purpose of the episcopate is to pass on the faith.

It seems to me that almost everything of importance about the role of bishops is contained in that phrase, and it is one that can help us therefore to reflect on our task in today’s world.

So, let’s explore that idea a little more. The primary role of bishops is to pass on the faith in these three ways:

- By proclaiming the faith to the world, as evangelists and prophets

- By teaching the faith within the church – guarding the faith we have received and interpreting it in each new generation and context

- By calling and equipping others to share in these tasks, both in the present for the future

And I would suggest that these are all things that we see in our Bible reading today.

For no sooner has Jesus commenced his public ministry in Nazareth and then throughout Galilee than he calls the first of the twelve disciples who, along with the subsequently appointed seventy-two, will go on to expand and continue his work, proclaiming the kingdom of God and enabling people to share in its blessings.

These things are the work of bishops, of those who are called to oversee the life of the Church both in time – across the generations – and in space – in all places and all nations of the world.

This, I would suggest, is the basis on which we should be considering the suitability and effectiveness of the ministry of our church: Do our ways of ordering the life of our churches contribute to the passing on of the faith?

That is, after all, what apostolic succession is really about: ensuring that the Christian faith is proclaimed and heard and received in every generation and every place, including in our nations, across the continent of Europe, in our generation.

That brings me to another theme on which I have been reflecting in recent months. Namely, what is the role of bishops in the context of Western European culture and society in the second quarter of the twenty-first century?

I am sure we are all deeply concerned about so many things that are going on in our world today. Just to list some of the most obvious:

- The climate crisis and its implications

- War in the Middle East and in Ukraine – and in other places too quickly forgotten like Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo

- Concerns over migration and the rise of political extremism across Europe

- The power of social media and the corruption of political discourse

- The rise of Artificial Intelligence and the potential for manipulation and disinformation – with all the threats these things bring to civil society and democracy.

Each of us can probably add more themes and make our own list!

In this extraordinary context in which we find ourselves, let me ask that question again: What are bishops for? What is the role of those who exercise oversight in the life of our churches (whether or not we call them bishops)?

And the answer to my mind is still the same. The role of bishops is to pass on the faith:

- To proclaim the good news of Jesus Christ and perspective of hope that it brings to use both individually and collectively

- To speak prophetically into the wider life of our culture and society, not as second-rate politicians but as those who have been commissioned to offer to the world an alternative way of being – one that is rooted in hope through Jesus Christ and not rooted in fear

- And to call and equip others to share in these tasks, both in the present for the future

The principal role of bishops is to teach the faith – to offer both an alternative to a self-defensive culture that fears the other, especially those who are outwardly different to us (something very relevant in today’s political climate) – and an alternative to the radical individualism and libertarianism that became dominant in western culture from the 1960s onwards.

This radical ideology (which is not the same as a healthy and positive liberalism which respects and honours different opinions) is now, I would suggest, beginning to collapse as people realise its destructive consequences and seek once more for purpose and meaning and order in place of chaos.

This makes our time one full of opportunity and full of risk. The history of our continent teaches us if nothing else that a vacuum of chaos and uncertainty can quickly be filled by powerful political forces.

We saw it in the 1930s and we may be seeing it again, fuelled by the power of social media, in the UK, Europe, the United States and elsewhere.

In this context, in our generation, the role of bishops – of those who are called to exercise oversight and leadership in the task of passing on the faith – is to speak prophetically of the hope that is ours in Christ and of the nearness of the kingdom of God.

To speak that is of the possibility of a different way of living which can move humanity away from the self-destructive path we are on and bring us back from the brink of disaster, politically, socially and environmentally.

Of course, bishops cannot do this on their own.

That task rests with the whole people of God, with the whole Body of Christ. And again, our task as the Body of Christ remains the same as it has always been namely, to proclaim and teach the faith and to call and commission others to share in that work.

That is what Jesus did, and it is the task he handed on to the apostles.

In the past few generations – and, let’s be honest, this is still going on – God has brought our churches in Western Europe to their knees, as people have drifted away, disillusioned by our failures and enticed by all that materialism has to offer.

It can be tempting for us to run after the world, to seek to adapt to its culture in the hope of winning people back. But the evidence is that this has not worked – and such a strategy means that in the end we have nothing distinctive to offer.

Sisters and brothers, as I reflect on the question of what bishops are for, I would suggest that the answer has not changed, and that the answer is in essence the same for us all, whatever our tradition or heritage.

Those who are charged with oversight and leadership in our churches are called to fulfil one central task - to pass on the faith in our generation:

- By proclaiming the faith to the world

- By teaching the faith to believers, and

- By calling and equipping and commissioning others to take on that task for the next generation.

I have spent some time focusing on these themes because it is out of this context that I believe we need to approach the challenges and opportunities that are facing us in today’s world.

That of course is very much what we are seeking to do through our Diocesan Vision and Strategy.

We are seeking to grow missional churches with missional leaders and missional disciples – and what is that about except passing on the faith to our generation and to the generations to come?

And what I see week by week as I go round churches across the Diocese is that God has got there before us!

God is at work bringing people to faith, as I see and hear in the testimonies of candidates of all ages and backgrounds, and especially among young adults from their teens into their thirties.

God is doing precisely what Jesus began to do in Galilee – calling people into discipleship, into following Jesus, by the work of the Holy Spirit and the preaching and teaching of the Gospel.

We are just playing catch-up and trying to join in with what God is already doing – and that is so exciting to see and be part of!

There is of course a long way to go, not least after the decline many of our churches experienced as a result of the pandemic, but to my mind there is no doubt that God is doing something new, and we need to make sure that we don’t get left behind!

And that brings me to comment finally on some of the big issues currently facing the Church of England, in what I would suggest is a time of both challenge and opportunity.

The first thing I want to focus on is the appointment of Bishop Sarah Mullaly as the next Archbishop of Canterbury and of course the first woman to take on that role.

I have warmly welcomed Bishop Sarah’s appointment, not only because of its momentous nature, but also because of the leadership qualities that she has demonstrated during her time as Bishop of London, including her willingness to work constructively with people from across the traditions of the Church of England.

It has been noticeable already that she has brought calmness and humility in her public statements and I can add in her dealings with her fellow bishops, and above all a commitment to seek to hold the Church together – both within England and across the wider Anglican Communion – as we wrestle with the challenges we face.

One of the biggest threats to holding the Church of England and the Anglican Communion together is of course the issues around Living in Love and Faith.

I will not say too much about that here but would warmly encourage all Diocesan Synod members to come to the meeting we will be holding in November, at which we will receive a presentation on where the LLF process has got to from the new Programme Director, the Revd Helen Fraser.

Hopefully by then, we will all have had a chance to read the papers (published just this week) which informed the discussions at the House of Bishops back in October, and which will also help shape whatever decisions will be made at the meeting of the House in December.

What I do want to acknowledge, however, is the huge sense of hurt and even of betrayal that many in the LGBT+ communities, together with others, have felt as a result of what the bishops are perceived to have done at their meeting in October, and the apparent contrast between this and what had been expected and hoped for by many, as a result of the LLF process over the last few months and years.

Sisters and brothers, we have not yet reached the end of this process, and there is much more to be said and done, but this sense of anger and disillusion has, I believe, been exacerbated by two main things.

The first is to do with the way the LLF process has been handled over the last few years, with an increasing sense of expectation being built up that there would be fundamental changes in the Church of England’s teaching and practice on same-sex relationships.

The problem was that this expectation was encouraged by poor practice over process and a failure to understand what would be required to achieve such change, in doctrinal, ecclesiological or liturgical terms.

This is a matter of deep regret to me, and I think the House of Bishops, of which I am of course, a member, has a lot to answer for what has occurred, especially in seeking to drive change without acknowledging the full reality of what would be required.

The second thing that has exacerbated the situation since the meeting of the House of Bishops last month, was the leaking of the papers that had been submitted to the House, prior to a residential meeting the LLF Working Groups, which had been working closely together across different traditions and perspectives over the last two years or so.

For transparency’s sake, I have been a member of one of those groups, but I was not able to attend the residential meeting in question.

This was not the first time that sensitive documents to do with LLF had been leaked, and as you will realise the effect of this is to increase mistrust as well as to make it much more difficult to explain the background to the papers and how it was that they so impacted the discussions and decisions of the bishops.

Synod, we are, as they say, where we are. And the first thing that we need to do now is to acknowledge how bruised some people are feeling, quite understandably, and probably also how exhausted we are all feeling as a result of the long and arduous process of LLF.

I do hope nevertheless that as many of Diocesan Synod as possible will come together in a spirit of prayerfulness and mutual concern, when we meet to hear and to discuss Helen’s presentation in November.

And that brings me back to my opening remarks about the role of bishops and indeed the task of the Church.

- To proclaim the faith to the world

- To teach the faith to believers

- To call, equip and commission others to take on that task for the next generation.

This is what we are really about, and how we handle the issues around LLF and how we behave towards one another as we do so are actually all part of one and the same thing.

Our words and our deeds are all part of our proclamation to the world.

They are what the world sees and hears, and that either helps or hinders people’s ability to receive and respond to the message of the Gospel.

I believe Bishop Sarah, as the Archbishop-elect of Canterbury, is both well-placed and committed to enabling the Church of England the Anglican Communion to move forward together.

Sisters and brothers, please above all pray for her, because the task before her is enormous and no-one could possibly bear it in their own strength! I will certainly be doing all I can to support her in this incredibly demanding and humanly impossible role.

And there is one area where I will be encouraging her and those responsible for leading the Church of England at the national level, to consider making something of a fresh start.

Later in this Synod, we will hear more about the Diocese’s budget for the next year, and also about the implications of the Diocesan Finances Review undertaken by the national church.

The outcome of that review has already been fixed for the next three years, but there is both an opportunity and a need to reconsider the parameters for both the amount of funding that is disbursed by the Archbishops’ Council from the Church Commissioners’ funds and, even more importantly, the way this is done.

Synod, I have raised this point before, and I will only mention it briefly here.

We are deeply grateful for the funds that have been made available to us through the Strategic Mission and Ministry Investment Board – the nearly £11 million pounds that will support the nine-year Called Together programme to grow missional churches with missional leaders who help grow missional disciples.

But across the Church of England, the majority of our Dioceses are facing huge financial challenges and are unable to maintain the number of stipendiary clergy that they need – even taking into account the falling numbers of such clergy, as retirements continue to outstrip ordinations.

The evidence is that God is at work in new ways up and down this country, and our Dioceses need to have the flexibility and the resources to respond to what God is doing.

The Church’s national arrangements for strategic funding have over the last ten years helped to focus people’s minds on the priority of mission – and that was much needed.

But we do now need a re-set that takes into account the changing landscape and the need for funds to be released to enable and sustain ministry in the parishes of the Church of England, ministry that will be exercised in a host of different ways, some more traditional and some in newer forms.

I hope and pray that under Archbishop Sarah’s leadership, the Church of England nationally will have the courage and the flexibility to release the resources that dioceses and parishes need to get on with the central tasks that God has given us to do:

- To proclaim the faith to the world

- To teach the faith to believers

- To call, equip and commission others to take on that task for the next generation.

Sisters and brothers, we live in a time of both challenge and opportunity. May God give us the courage to rise to the challenge and to seize the opportunity.

Thank you.

The Rt Revd Dr Jonathan Gibbs

Bishop of Rochester

8 November 2025